Lie on left side with top leg on chair. Slowly raise the bottom leg up to the chair seat. Hold leg up for six seconds. Do six repeats and then switch sides.

Lie on left side with top leg on chair. Slowly raise the bottom leg up to the chair seat. Hold leg up for six seconds. Do six repeats and then switch sides.

Tuesday, July 31, 2007

Hip Adduction

Hip Adduction

Lie on left side with top leg on chair. Slowly raise the bottom leg up to the chair seat. Hold leg up for six seconds. Do six repeats and then switch sides.

Lie on left side with top leg on chair. Slowly raise the bottom leg up to the chair seat. Hold leg up for six seconds. Do six repeats and then switch sides.

Lie on left side with top leg on chair. Slowly raise the bottom leg up to the chair seat. Hold leg up for six seconds. Do six repeats and then switch sides.

Lie on left side with top leg on chair. Slowly raise the bottom leg up to the chair seat. Hold leg up for six seconds. Do six repeats and then switch sides.

Monday, July 30, 2007

Quadricep Set --Knee Extension

Sunday, July 29, 2007

Hip Abduction

Hip Abduction

Lie on left side with bottom knee bent, Raise top leg. Keep knee straight and toes pointed forward. Do not let top hip roll backward. Hold this position for six seconds. Do six repeats and then switch sides. Progress slowly to just under 1 Kg at the ankle.(Check weights with physiotherapist.)

Saturday, July 28, 2007

Straight Leg Raise -- With Internal and External Rotation

Straight Leg Raise -- With Internal and External Rotation

Lie on back, with right knee bent and foot flat. Move left foot to 10 o'clock position. Lift left leg in air about thirty centimetres (twelve inches). Keep your left knee straight. Hold this position for six seconds. Then move left foot to 2 o'clock position. Lift the leg up 30 centimetres and hold. Repeat this exercise six times and then switch legs. Slowly add weights to ankle.(Check weights with physiotherapist.)

Friday, July 27, 2007

Straight Leg Raise --Knee Extension Raise

Straight Leg Raise --Knee Extension Raise

Lie on back, with right knee bent and right foot flat on ground. Gradually lift the left leg up about thirty centimetres (twelve inches) in the air. Keep the knee straight and the toes pointed up. Hold this elevated position for six seconds. Slowly return leg to ground and start again. Repeat six times, and then start again by lifting the right leg. Slowly add weights to ankles to increase resistance.

Lie on back, with right knee bent and right foot flat on ground. Gradually lift the left leg up about thirty centimetres (twelve inches) in the air. Keep the knee straight and the toes pointed up. Hold this elevated position for six seconds. Slowly return leg to ground and start again. Repeat six times, and then start again by lifting the right leg. Slowly add weights to ankles to increase resistance.

Thursday, July 26, 2007

Fitness for Life

Fitness for Life

Follow this expert advice to get back on the exercise wagon—and make workouts a routine part of your life.

Follow this expert advice to get back on the exercise wagon—and make workouts a routine part of your life.

Eighty-eight percent of Health subscribers want to make exercise part of their daily lives, according to our recent Women in Motion study. So why do half of the people who begin exercise programs drop out before the 6-month mark? One reason is lack of motivation. If exercise is on the bottom of your to-do list, follow these five easy tips to make exercise a daily habit.

Treat your workouts like a standing appointment.Things happen, and workouts are usually the first thing cut if your time is short. If you write down your workouts in your daily planner, you’re more likely to view exercise as a non-negotiable.

Customize your workouts based on your mood.If you’re tired, instead of lifting weights, try shooting some hoops. Stressed? Try yoga or Pilates. By fitting the workout with your mood, you’ll increase your workout variety. And variety is vital to staying motivated. “You also need a backup plan if the gym is too crowded,” says Dr. John Raglin, professor of kinesiology at Indiana University. “You don’t want to increase an already frustrating day if someone is on your favorite machine.” Take time to plan out several workout routines so you always have a plan B.

Make your exercise goals realistic.“It takes the average adult 15 years to gain 10 to 15 pounds,” Raglin says. “You can’t expect to lose it all in 2 months.” Guilt and weight loss are not effective long-term motivators. Change your perspective to include exercising for good health, not simply for weight loss. Set smaller goals, such as running a 5K or joining a tennis league. Once you accomplish several smaller goals, you’ll be more likely to stay motivated to train for that marathon you’ve always wanted to run.

Make your exercise goals realistic.“It takes the average adult 15 years to gain 10 to 15 pounds,” Raglin says. “You can’t expect to lose it all in 2 months.” Guilt and weight loss are not effective long-term motivators. Change your perspective to include exercising for good health, not simply for weight loss. Set smaller goals, such as running a 5K or joining a tennis league. Once you accomplish several smaller goals, you’ll be more likely to stay motivated to train for that marathon you’ve always wanted to run.

Find an exercise buddy.Exercise can be a challenge—one you don’t want to conquer alone. Friends can hold you accountable and give you increased obligation not to skip your workouts. “Exercising with other people gives you a connection, “ says Cotton, who is also a spokesman for the American Council on Exercise.

Reward yourself.You’ll do anything for a double scoop of butter pecan ice cream, right? So if you exercise four times in a given week, treat yourself. If a massage is more up your alley, schedule an appointment. Figure out which rewards will motivate you. Once you accomplish your exercise goals, be sure to take the time to reward yourself for a job well done.

If you’ve experienced exercise burnout, it may seem hard to get back in the saddle. Sit down and analyze what caused your exercise program to fail. Were you bored? Did you quit when you didn’t reach your weight-loss goal? Do you have too many work and home commitments at odds, causing you stress? Were your workouts too hard, making you dread exercise? Once you’ve pinpointed what caused you to fail, make a new exercise plan with realistic goals. “You will gain new insight every time you fail,” Raglin says. “Fail and try again. You have plenty of chances.”

Sunday, July 22, 2007

ACL Reconstruction

When you twist your knee or fall on it, you can tear a stabilizing ligament that connects your thighbone to the shinbone. An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) unravels like a braided rope when it's torn and does not heal on its own. Fortunately, reconstruction surgery can help many people recover their full function after an ACL tear.

ACL TEAR

Ligaments are tough, non-stretchable fibers that hold your bones together. The cruciate ligaments in your knee joints crisscross to give you stability on your feet. People often tear the ACL by changing direction rapidly, slowing down from running or landing from a jump. Young people (age 15-25) who participate in basketball and other sports that require pivoting are especially vulnerable. You might hear a popping noise when your ACL tears. Your knee gives out and soon begins to hurt and swell.

First treatment includes rest, ice compression and elevation (RICE) plus a brace to immobilize the knee, crutches and pain relievers. Get to your doctor right away to evaluate your condition.

EVALUATION

Your doctor may conduct physical tests and take X-rays to determine the extent of damage to your ACL. Most of the time, you need reconstruction surgery. Your doctor replaces the damaged ACL with strong, healthy tissue taken from another area near your knee. A strip of tendon from under your kneecap (patellar tendon) or hamstring may be used. Your doctor threads the tissue through the inside of your knee joint and secures the ends to your thighbone and shinbone.

In a few cases when the ACL is torn cleanly from the bone it can be repaired. Less active people may be treated nonsurgically with a program of muscle strengthening.

Your doctor may conduct physical tests and take X-rays to determine the extent of damage to your ACL. Most of the time, you need reconstruction surgery. Your doctor replaces the damaged ACL with strong, healthy tissue taken from another area near your knee. A strip of tendon from under your kneecap (patellar tendon) or hamstring may be used. Your doctor threads the tissue through the inside of your knee joint and secures the ends to your thighbone and shinbone.

In a few cases when the ACL is torn cleanly from the bone it can be repaired. Less active people may be treated nonsurgically with a program of muscle strengthening.

OUTCOME

Successful ACL reconstruction surgery tightens your knee and restores its stability. It also helps you avoid further injury and get back to playing sports. After ACL reconstruction, you'll need to do rehabilitation exercises to gradually return your knee to full flexibility and stability. Building strength in your thigh and calf muscles helps support the reconstructed structure. You may need to use a knee brace for awhile and will probably have to stay out of sports for about one year after the surgery.

Successful ACL reconstruction surgery tightens your knee and restores its stability. It also helps you avoid further injury and get back to playing sports. After ACL reconstruction, you'll need to do rehabilitation exercises to gradually return your knee to full flexibility and stability. Building strength in your thigh and calf muscles helps support the reconstructed structure. You may need to use a knee brace for awhile and will probably have to stay out of sports for about one year after the surgery.

Saturday, July 21, 2007

ACL Injury: Potential Operative Complications

The incidence of infection after arthroscopic ACL reconstruction has a reported range of 0.2 percent to 0.48 percent. There have also been several reported deaths linked to bacterial infection from allograft tissue due to improper procurement and sterilization techniques.

Allografts specifically are associated with risk of viral transmission, including HIV and Hepatitis C, despite careful screening and processing. The chance of obtaining a bone allograft from an HIV-infected donor is calculated to be less than 1 in a million.

Rare risks include bleeding from acute injury to the popliteal artery (overall incidence is 0.01 percent) and weakness or paralysis of the leg or foot. It is not uncommon to have numbness of the outer part of the upper leg next to the incision, which may be temporary or permanent.

A blood clot in the veins of the calf or thigh is a potentially life-threatening complication. A blood clot may break off in the bloodstream and travel to the lungs, causing pulmonary embolism or to the brain, causing stroke. This risk of deep vein thrombosis is reported to be approximately 0.12 percent.

Recurrent instability due to rupture or stretching of the reconstructed ligament or poor surgical technique (reported to be as low as 2.5 percent and as high as 10 percent) is possible. Knee stiffness or loss of motion has been reported at between 5 percent and 25 percent. Rupture of the patellar tendon (patellar tendon autograft) or patella fracture (patellar tendon or quadriceps tendon autografts) may occur due to weakening at the site of graft harvest.

In young children or adolescents with ACL tears, early ACL reconstruction creates a possible risk of growth plate injury, leading to bone growth problems. The ACL surgery can be delayed until the child is closer to reaching skeletal maturity. Alternatively, the surgeon may be able to modify the technique of ACL reconstruction to decrease the risk of growth plate injury.

Postoperative anterior knee pain is especially common after patellar tendon autograft ACL reconstruction. The incidence of pain behind the kneecap varies between 4 percent and 56 percent in studies, whereas the incidence of kneeling pain may be as high as 42 percent after patellar tendon autograft ACL reconstruction.

Friday, July 20, 2007

ACL Injury: Operative Procedure

Before any surgical treatment, the patient is usually sent to physical therapy. Patients who have a stiff, swollen knee lacking full range of motion at the time of ACL surgery may have significant problems regaining their motion after surgery It usually takes three or more weeks from the time of injury to achieve full range of motion. It is also recommended that some ligament injuries be braced and allowed to heal prior to ACL surgery.

The patient, the surgeon and the anesthesiologist select the anesthesia used for surgery. Patients may benefit from an anesthetic block of the nerves of the leg to decrease postoperative pain. The surgery usually begins with an examination of the patient's knee while the patient is relaxed due the effects of anesthesia. This final examination is used to verify that the ACL is torn and also to check for looseness of other knee ligaments that may need to be repaired during surgery or addressed postoperatively. If the physical exam strongly suggests the ACL is torn, the selected tendon is harvested (for an autograft) or thawed (for an allograft) and the graft is prepared to the correct size for the patient.

After the graft has been prepared, the surgeon places an arthroscope into the joint. Small (one-centimeter) incisions called portals are made in the front of the knee to insert the arthroscope and instruments and the surgeon examines the condition of the knee.

Meniscus and cartilage injuries are trimmed or repaired and the torn ACL stump is then removed. In the most common ACL reconstruction technique, bone tunnels are drilled into the tibia and the femur to place the ACL graft in almost the same position as the torn ACL. A long needle is then passed through the tunnel of the tibia, up through the femoral tunnel, and then out through the skin of the thigh. The sutures of the graft are placed through the eye of the needle and the graft is pulled into position up through the tibial tunnel and then up into the femoral tunnel. The graft is held under tension as it is fixed in place using interference screws, spiked washers, posts or staples. The devices used to hold the graft in place are generally not removed. Variations on this surgical technique include the "two-incision" and "over-the-top" types of ACL reconstructions, which may be used because of the preference of the surgeon or special circumstances (revision ACL reconstruction, open growth plates).

Before the surgery is complete, the surgeon will probe the graft to make sure it has good tension , verify that the knee has full range of motion and perform tests such as the Lachman's test to assess graft stability. The skin is closed and dressings (and perhaps a postoperative brace and cold therapy device, depending on surgeon preference) are applied. The patient will usually go home on the same day of the surgery.

Thursday, July 19, 2007

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE

TREATMENT OPTIONS FOR OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE KNEE

In order to better understand the treatment options for osteoarthritis of the knee, it is important to understand basic knee anatomy and the function of articular cartilage. Please review the sections on knee anatomy as well as the introduction to osteoarthritis of the knee before reading this section.

Osteoarthritis is a chronic disorder that gradually progresses over time. In the knee, the symptoms of osteoarthritis may include pain, stiffness, swelling, "locking," and "catching". These symptoms may progress to an eventual limitation of activities whether it is an inability to run or an inability to walk up and down stairs. There is no cure for osteoarthritis of the knee. The therapies currently available are used only to treat the symptoms.

The 3 main goals of treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee are:

1. To decrease pain2. To maintain or improve range of motion of the knee (ability to bend and straighten the knee)3. To maintain or improve function (ability to climb stairs, run, jump, play sports, etc.)

There are many treatment options available and often, many different types of therapy must be used together to improve symptoms. The severity of an individual's symptoms

The treatment options available to individuals with osteoarthritis of the knee can be divided into the following categories;

Education and Biomechanical Treatment Options

• Educational Resources

• Lifestyle Modifications

• Physical Therapy

• Supportive Devices (Canes, Braces, Orthotics)

Medications and Nutritional Supplements

• Nutritional Supplements and Nutritional Supplement Fact Sheet

• Oral Medications (Pills)

• Topical Medications (Ointments and Creams)

• Knee Injections

Surgical Treatment Options

• Introduction to Surgical Treatment Options for Osteoarthritis of the Knee

• Arthroscopic Knee Surgery and Abrasion Arthroplasty• Osteotomy

• Total Knee Replacement Surgery

• Partial Knee Replacement Surgery

• Articular Cartilage Transplantation and Cellular Implant Surgery

Osteoarthritis is a chronic disorder that gradually progresses over time. In the knee, the symptoms of osteoarthritis may include pain, stiffness, swelling, "locking," and "catching". These symptoms may progress to an eventual limitation of activities whether it is an inability to run or an inability to walk up and down stairs. There is no cure for osteoarthritis of the knee. The therapies currently available are used only to treat the symptoms.

The 3 main goals of treatment for osteoarthritis of the knee are:

1. To decrease pain2. To maintain or improve range of motion of the knee (ability to bend and straighten the knee)3. To maintain or improve function (ability to climb stairs, run, jump, play sports, etc.)

There are many treatment options available and often, many different types of therapy must be used together to improve symptoms. The severity of an individual's symptoms

The treatment options available to individuals with osteoarthritis of the knee can be divided into the following categories;

Education and Biomechanical Treatment Options

• Educational Resources

• Lifestyle Modifications

• Physical Therapy

• Supportive Devices (Canes, Braces, Orthotics)

Medications and Nutritional Supplements

• Nutritional Supplements and Nutritional Supplement Fact Sheet

• Oral Medications (Pills)

• Topical Medications (Ointments and Creams)

• Knee Injections

Surgical Treatment Options

• Introduction to Surgical Treatment Options for Osteoarthritis of the Knee

• Arthroscopic Knee Surgery and Abrasion Arthroplasty• Osteotomy

• Total Knee Replacement Surgery

• Partial Knee Replacement Surgery

• Articular Cartilage Transplantation and Cellular Implant Surgery

OSGOOD - SCHLATTER'S KNEE PAIN

This section covers Osgood-Schlatter's Knee Pain that occurs as a result of overuse ("too much activity, too soon"). In order to better understand Osgood-Schlatter's Knee Pain it is important to understand the anatomy and function of the knee and the patellar tendon.

The patellar tendon is a thick rope-like structure that connects the bottom of the kneecap (patella) to the top of the large shin bone (tibia). The powerful muscles on the front of the thigh, the quadriceps muscles, straighten the knee by pulling at the patellar tendon via the patella. OSKP is caused by inflammation (irritation) where the patellar tendon attaches to the tibia.

Osgood-Schlatter's Knee Pain (OSKP), also known as Osgood-Schlatter's disease, is common in rapidly growing, active young teenagers and pre-teenagers. Pain from OSKP is usually felt 2-3 finger widths below the bottom of the patella. There may be swelling in the area and it can be sensitive to touch. The pain can be mild or in some cases the pain can be so bad that it prevents athletes from playing their sport.

OSKP is usually occurs as a result of overdoing an activity and placing too much stress on growing bones. Activities that include a lot of running, jumping or stopping and starting can make OSKP worse. OSKP can be prevented by easing into these types of activities and by using good training techniques. Off-season strength training of the legs, particularly the quadriceps muscles, can also help.

Examination techniques that detect tenderness and swelling at the attachment site of the patellar tendon to the tibia are helpful in determining if someone has OSKP. X-rays are occasionally done to make sure that the patellar tendon does not have any calcium in it. Other tests such as diagnostic ultrasound or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are rarely required to rule out more extensive damage to the patellar tendon.

The treatment of OSKP may include relative rest, icing, medications to reduce inflammation and pain, stretching and strengthening exercises. Rarely is complete rest or the use of a knee brace or cast necessary. Sometimes OSKP will even go away on it's own. Doctors and physiotherapists trained in treating this type of overuse injury can outline a treatment plan specific to each individual.

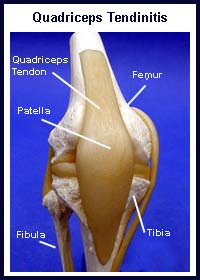

QUADRICEPS TENDINITIS

In order to better understand quadriceps tendinitis it is important to understand the anatomy and function of the knee and the quadriceps tendon.

The kneecap (patella) is a small bone in the front of the knee. It glides up and down a groove in the thigh bone (femur) as the knee bends and straightens. Tendons connect muscles to bone. The strong quadriceps muscles on the front of the thigh attach to the top of the patella via the quadriceps tendon. This tendon covers the patella and continues down to form the "rope-like" patellar tendon. The patellar tendon in turn, attaches to the shin bone (tibia). The quadriceps muscles, straighten the knee by pulling at the patella via the quadriceps tendon. Quadriceps tendinitis is the term used to describe inflammation of the quadriceps tendon.

Quadriceps tendinitis usually occurs as a result of overdoing an activity and placing too much stress on the quadriceps tendon before it is strong enough to handle the stress. This overuse results in 'micro tears' in the quadriceps tendon which leads to inflammation and pain. Over time damage to the quadriceps tendon can occur. In extreme cases, the quadriceps tendon may become damaged to the point of complete rupture.

Quadriceps tendinitis is common in people involved in activities that include a lot of running, jumping, stopping and starting. Pain from quadriceps tendinitis is felt in the area just above the patella. There may be swelling in and around the quadriceps tendon and it may be sensitive to touch. The pain can be mild or in some cases the pain can be so bad that it prevents athletes from playing their sport.

Examination techniques that detect tenderness and swelling in or around the quadriceps tendon are helpful in determining if someone has quadriceps tendinitis. X-rays are occasionally done to make sure that the quadriceps tendon does not have any calcium in it. Other tests such as diagnostic ultrasound or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are sometimes used to rule out more extensive damage to the quadriceps tendon.

Treatment of quadriceps tendinitis may include relative rest, icing, medications to reduce inflammation and pain, stretching and strengthening exercises. Quadriceps tendinitis may be prevented by easing into jumping or running sports and by using good training techniques. Off-season strength training of the legs, particularly the quadriceps muscles, can also help. Doctors and physiotherapists trained in treating this type of overuse injury can outline a treatment plan specific to each individual.

The kneecap (patella) is a small bone in the front of the knee. It glides up and down a groove in the thigh bone (femur) as the knee bends and straightens. Tendons connect muscles to bone. The strong quadriceps muscles on the front of the thigh attach to the top of the patella via the quadriceps tendon. This tendon covers the patella and continues down to form the "rope-like" patellar tendon. The patellar tendon in turn, attaches to the shin bone (tibia). The quadriceps muscles, straighten the knee by pulling at the patella via the quadriceps tendon. Quadriceps tendinitis is the term used to describe inflammation of the quadriceps tendon.

Quadriceps tendinitis usually occurs as a result of overdoing an activity and placing too much stress on the quadriceps tendon before it is strong enough to handle the stress. This overuse results in 'micro tears' in the quadriceps tendon which leads to inflammation and pain. Over time damage to the quadriceps tendon can occur. In extreme cases, the quadriceps tendon may become damaged to the point of complete rupture.

Quadriceps tendinitis is common in people involved in activities that include a lot of running, jumping, stopping and starting. Pain from quadriceps tendinitis is felt in the area just above the patella. There may be swelling in and around the quadriceps tendon and it may be sensitive to touch. The pain can be mild or in some cases the pain can be so bad that it prevents athletes from playing their sport.

Examination techniques that detect tenderness and swelling in or around the quadriceps tendon are helpful in determining if someone has quadriceps tendinitis. X-rays are occasionally done to make sure that the quadriceps tendon does not have any calcium in it. Other tests such as diagnostic ultrasound or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) are sometimes used to rule out more extensive damage to the quadriceps tendon.

Treatment of quadriceps tendinitis may include relative rest, icing, medications to reduce inflammation and pain, stretching and strengthening exercises. Quadriceps tendinitis may be prevented by easing into jumping or running sports and by using good training techniques. Off-season strength training of the legs, particularly the quadriceps muscles, can also help. Doctors and physiotherapists trained in treating this type of overuse injury can outline a treatment plan specific to each individual.

PREPATELLAR BURSITIS

PREPATELLAR BURSITIS

This section covers bursitis of the prepatellar bursa that occurs after an injury or trauma (traumatic prepatellar bursitis). In order to better understand traumatic prepatellar bursitis it is important to understand the anatomy and function of the knee and the patella. Please review the section on knee anatomy before reviewing this section.

The kneecap (patella) is a small bone in the front of the knee. It glides up and down a groove in the thighbone (femur) as the knee bends and straightens. The patellar tendon is a thick, ropelike structure that connects the bottom of the patella to the top of the large shinbone (tibia). The powerful muscles on the front of the thigh, the quadriceps muscles, straighten the knee by pulling at the patellar tendon via the patella.

A bursa (pl. bursae) is a small fluid filled sac that decreases the friction between two tissues. Bursae also protect bony structures. There are many different bursae around the knee but the one that is most commonly injured is the bursa in front of the patella, the prepatellar bursa.

The prepatellar bursa is usually very thin. When irritated or injured the prepatellar bursa can fill with fluid or blood and become large and painful. If repeatedly irritated or injured, the walls of the bursa may thicken and have irregular areas of scar tissue that are often mistaken as "bone chips". Calcium may also collect inside the bursa.

After a direct blow to the front of the knee the prepatellar bursa can become swollen. This can occur immediately or over a couple of hours. The degree of swelling can vary. The front of the knee is usually very painful to touch and it can also be painful to move. In addition, the area around the prepatellar bursa may be warm. If there is significant swelling or pain X-rays are usually performed to rule out a broken or chipped patella.

Depending on the severity of the injury, the treatment of traumatic prepatellar bursitis may include resting the knee, applying ice packs to the area, light compression of the knee with a tensor bandage and elevation of the injured leg. Medications to help reduce the swelling and pain may also be required. If there is a large amount of swelling and the knee is uncomfortable the bursa may need to be drained by a doctor.

After the swelling comes down and the bursa is less painful, padding the area may be required for some types of work, sports and recreational activities like gardening. In rare cases surgery is required to remove a prepatellar bursa that remains swollen or is repeatedly irritated or injured.

Complications of traumatic prepatellar bursitis include repeated irritation or injury, persistent pain and/or swelling or infection in the bursa. These complications require different types of treatment. Doctors and physiotherapists trained in treating these types of injuries can outline an individualized treatment for traumatic prepatellar bursitis.

ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME

ILIOTIBIAL BAND SYNDROME

Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is a common cause of pain in the outer (lateral) side of the knee. ITBS is also a common overuse injury in runners. In order to better understand ITBS it is important to understand the anatomy and function of the knee. Please review the section on knee anatomy before reviewing this section.

The knee joint is made up of four bones, which are connected by muscles, ligaments, and tendons. The femur is the large bone in the thigh. The tibia is the large shinbone. The fibula is the smaller shinbone, located next to the tibia. The patella, otherwise known as the kneecap, is the small bone in the front of the knee. It slides up and down in a groove in the femur (the femoral groove) as the knee bends and straightens.

The iliotibial band is a belt-like band of tissue that runs from a muscle on the outer side of the hip, the tensor fascia lata, down the outer side of the thigh and attaches to the outer side of the patella and the tibia. Other muscles of the hip also attach to the iliotibial band and together with the tensor fascia lata control outward hip movement (abduction). The iliotibial band also provides stability to the lateral side of the knee.

A bursa (pl. bursae) is a small fluid filled sac that decreases the friction between two tissues. Bursae also protect bony structures. There are many different bursae around the knee. There is a bursa that protects the iliotibial band from the underlying femur. Normally, a bursa has very little fluid in it but if it becomes irritated it can fill with fluid and become painful.

The end of the femur has two large projections called epicondyles. When the knee is fully straight (extended) the iliotibial band lies in front of the lateral epicondyle of the femur. As the knee bends (flexes), the iliotibial band slips over the lateral epicondyle and ends up behind it. Friction occurs where the iliotibial band passes over the lateral femoral condyle. This friction can result in inflammation of the bursa that separates the iliotibial band from the underlying bone, or the iliotibial band itself.

ITBS is usually the result of overuse or over training. ITBS is found predominantly in runners and is often associated with changes in training such as a sudden increase in distance or intensity. Running on uneven surfaces such as the shoulder of the road may also cause ITBS, most commonly in the "downhill" leg. Other predisposing factors include prominent lateral femoral condyles or tight iliotibial bands.

As mentioned above, the pain from ITBS is felt on the lateral aspect of the knee. The pain may also radiate up the lateral aspect of the thigh or around to the front of the knee. The pain is usually made worse by repetitive flexion and extension movements of the knee. Initially, the pain may only be felt during a run. If training continues, pain may be felt even at rest.

On examination of the knee the iliotibial band is usually tight. There is often tenderness of the iliotibial band where it passes over the lateral femoral condyle. When pressure is applied to the lateral femoral condyle and the knee is repetitively flexed and extended the pain that is felt during training can often be reproduced. X-rays are usually normal.

Treatment of ITBS may include relative rest, icing, medications to reduce inflammation and pain, stretching, and strengthening exercises. Doctors and physiotherapists trained in treating this type of overuse injury can outline a treatment plan specific to each individual.

Meniscal Injuries

Meniscal injuries are often associated with a ligament tear of the knee. An injury to one of the main supporting ligaments of the knee can result in an unstable knee increasing the chance of tearing a meniscus. When a meniscus is injured the knee often becomes painful and/or swollen. The pain is usually made worse by specific movements such as bending or twisting the knee. Certain maneuvers may produce a "click", "pop" or sharp pain which is often localized to the medial or lateral joint line (the space between the thigh bone and the shin bone). Swelling can be caused from irritation of the knee joint by the torn meniscus.

X-rays cannot detect meniscal injuries but are useful to rule out wear and tear arthritis (osteoarthritis), loose pieces of bone or a broken bone which may mimic a "torn cartilage". Occasionally a special test called Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is required. Arthroscopic surgery is helpful in both the diagnosis and treatment of these injuries.

Initially the treatment of meniscus injuries may include activity modification, ice, medication (to reduce pain and/or swelling) and physiotherapy. If a torn meniscus does not heal, and pain, swelling or intermittent catching persists, arthroscopic surgery may be necessary. Arthroscopic surgery is usually required if the knee remains locked.

MENISCUS (CARTILAGE) INJURIES

MENISCUS (CARTILAGE) INJURIES

The meniscus is a "C" shaped "shock absorber" which lies between the thigh bone (femur) and the shin bone (tibia). There is a meniscus on the inner (medial) side of the knee and one on the outer (lateral) side of the knee. Injuries to either the medial meniscus or the lateral meniscus are common and are often referred to as a "torn cartilage". Injuries to the menisci often result in pain and swelling in the knee. If the torn piece of meniscus is large, it may cause the knee to catch, lock, or give way (For more anatomy, click here).

Catching occurs when the torn fragment briefly lodges between the bones then works its way out. If the fragment does not work its way out the knee will remain "locked", meaning the knee cannot fully bend or straighten. Locking can be brief (lasting seconds or minutes) or persistent (lasting weeks). Giving way occurs when the torn piece of meniscus slips out of place which causes pain and reflex relaxation of the thigh muscles. When the muscles relax the knee "gives way" or "gives out."

The most common cause of sudden (acute) meniscal tears in younger people is a combined loading and twisting injury to the knee. However, the medial or lateral meniscus can undergo a degenerative tear without any significant injury to the knee. The medial meniscus is more frequently injured than the lateral meniscus.

Wednesday, July 18, 2007

What is knee bursitis?

The knee joint is surrounded by three major bursae. At the tip of the knee, over the kneecap bone, is the prepatellar bursa. This bursa can become inflamed (prepatellar bursitis) from direct trauma to the front of the knee. This commonly occurs with prolonged kneeling position. It has been referred to as "housemaid's knee," "roofer's knee," and "carpetlayer's knee," based on the patient's associated occupational histories. It can lead to varying degrees of swelling, warmth, tenderness, and redness in the overlying area of the knee. As compared with knee joint inflammation (arthritis), it is usually only mildly painful. It is usually associated with significant pain when kneeling and can cause stiffness and pain with walking. Also, in contrast to problems within the knee joint, the range of motion of the knee is frequently preserved.

Prepatellar bursitis can occur when the bursa fills with blood from injury. It can also be seen in rheumatoid arthritis and from deposits of crystals, as seen in patients with gouty arthritis and pseudogout. The prepatellar bursa can also become infected with bacteria (septic bursitis). When this happens, fever may be present. This type of infection usually occurs from breaks in the overlying skin or puncture wounds. The bacteria involved in septic bursitis of the knee are usually those that normally cover the skin, called staphylococcus. Rarely, a chronically inflamed bursa can become infected by bacteria traveling through the blood.

Tuesday, July 17, 2007

Choice of Graft

Choice of Graft

No ideal graft for ACL reconstruction exists. All graft choices have advantages and disadvantages.

Patella tendon grafts are still considered the historical "gold standard" for knee stability by surgeons, however they suffer a slightly higher complication rate.

Hamstring grafts had initial problems with fixation slippage. Modern fixation methods of hamstrings avoid graft slippage, producing outcomes that are the same in terms of knee stability with easier rehabilitation, less anterior knee pain and less joint stiffness.

The main factors in knee stability are correct graft placement by the surgeon and treatment of other menisco-ligament injuries in the knee, rather than choice of graft

Allograft

Allograft

An ACL, patellar tendon, anterior tibialis tendon, or achilles tendon may be harvested from a cadaver and used as an allograft in reconstruction. The achilles tendon is so large it needs to be shaved to fit within the cavity inside the knee. This method has the benefit that the most painful part of the surgery, the harvesting of tendon tissue, is avoided. However, there is a slight chance of rejection which would lead to another surgery to remove the graft and replace it again.

Allografts are often irradiated to remove infectious agents. There is a risk of weakening the selected tendon, although for ACL surgery the weakened tendon is still as strong or about as strong as the ligament being replaced. Even with the extensive and redundant screening process for donor grafts, there is still a risk of infection, which would be grounds to remove the graft. Therefore, this option runs the largest health risk.

Monday, July 16, 2007

Hamstring Tendon

Hamstring Tendon

For this procedure, the gracilis and semitendinosus tendons from the hamstring of the injured knee are the source of the graft. A long piece (about 25 cm) is removed from each of two tendons. The tendon segments are folded and braided together to form a quadruple thickness strand for the replacement graft. The braided segment is threaded through the heads of tibia and femur and its ends fixated with screws on the opposite sides of the two bones.

Unlike the patellar tendon, the hamstring tendon's fixation to the bone can be affected by motion in the post-operative phase. Therefore, following surgery, a brace is often used to immobilize the knee for one to two weeks while the most critical healing takes place. Evidence suggests that the hamstring tendon graft does just as well, or nearly as well, as the patellar tendon graft in the long-term[citation needed].

This main surgical wound is over the upper proximal shin which would avoid the typical pain sensation when one kneel down. Besides, the wound is typically smaller than the patellar tendon graft and hence less pain after the operation. As a result, patient undergone this operation typically discharge from hospital within 2 days after surgery.

Patellar Tendon

Patellar Tendon

The patellar tendon connects the patella (kneecap) to the tibia (shin). Generally the graft is taken from the injured knee, but in some circumstances (such as a second operation) the other knee may be used. The middle third of the tendon is used, with bone fragments on each end removed. The graft is then threaded through holes drilled in the tibia and femur, and finally screwed into place.

The graft is slightly larger than a hamstring graft, however graft size is not a determinant of outcome. The most important factor in determining the outcome is correct graft placement.

The disadvantages include: 1. more wound pain , 2. more prominent scar as compared to hamstring tendon operation , 3. risk of fracture of patella during harvesting of this graft resulting in significant complication , 4. increased risk of tendonitis.

Sunday, July 15, 2007

Types of grafts

There are three types common grafting for knee and are as below:-

- Patellar tendon

- Hamstring tendon

- Allograft

These will be discussed in detail later.

Saturday, July 14, 2007

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACL reconstruction) is surgical graft replacement of a torn anterior cruciate ligament in the knee. Because the ACL does not heal on its own, an ACL reconstruction requires a tissue graft. The torn ligament is removed from the knee before the graft is inserted. The types of surgery differ mainly in the type of graft that is used. In all cases, part of the surgery is done arthroscopically

Friday, July 13, 2007

Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL)

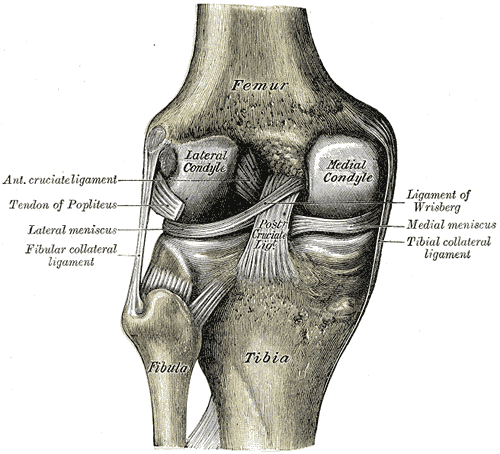

The posterior cruciate ligament (or PCL) is one of the four major ligaments of the knee. It connects the posterior intercondylar area of the tibia to the medial condyle of the femur. This configuration allows the PCL to resist forces pushing the tibia posteriorly relative to the femur.

Injury

The posterior drawer test is used by doctors to detect injury to the PCL.

The posterior drawer test is used by doctors to detect injury to the PCL.

Surgery to repair the Posterior Cruciate ligament is controversial due to its placement and technical difficulty

Thursday, July 12, 2007

Medial Collateral Ligament (MCL)

The medial collateral ligament or MCL (or tibial collateral ligament) is one of the four major ligaments of the knee.

It resists forces pushing the knee medially (towards the body), which would otherwise produce valgus deformity.

The medial collateral ligament is a broad, flat, membranous band, situated slightly posterior on the medial side of the knee joint.

It is attached proximally to the medial condyle of femur immediately below the adductor tubercle; below to the medial condyle of the tibia and medial surface of its body.

The fibers of the posterior part of the ligament are short and incline backward as they descend; they are inserted into the tibia above the groove for the semimembranosus muscle.

The anterior part of the ligament is a flattened band, about 10 cm. long, which inclines forward as it descends.

It is inserted into the medial surface of the body of the tibia about 2.5 cm. below the level of the condyle.

Crossing on top of the lower part of the MCL is the pes anserinus, the joined tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendinosus muscles; a bursa is interposed between the two.

The MCL's deep surface covers the inferior medial genicular vessels and nerve and the anterior portion of the tendon of the semimembranosus muscle, with which it is connected by a few fibers; it is intimately adherent to the medial meniscus

Fibular Collateral Ligament

The Fibular Collateral Ligament (external lateral or long external lateral ligament) is a strong, rounded, fibrous cord, attached, above, to the back part of the lateral condyle of the femur, immediately above the groove for the tendon of the Popliteus; below, to the lateral side of the head of the fibula, in front of the styloid process.

The greater part of its lateral surface is covered by the tendon of the Biceps femoris; the tendon, however, divides at its insertion into two parts, which are separated by the ligament.

Deep to the ligament are the tendon of the Popliteus, and the inferior lateral genicular vessels and nerve.

The ligament has no attachment to the lateral meniscus.

Wednesday, July 11, 2007

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury

Although there are many ACL injuries,the ACL is next to the most commonly injured knee ligament, the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL).[1] and commonly injured by athletes. The ACL is often torn during sudden dislocation of the knee, twisting, hyperextending. It is a very common injury in skiing, skating and football due to the enormous amount of pressure, weight and number of blows the knee must withstand.

Diagnosis

The Lachman test is supported by most authorities to be the most reliable and sensitive maneuver for the diagnosis of an ACL tear.

Anterior Cruciate Ligament

Anterior Cruciate Ligament

The anterior cruciate ligament (or ACL) is one of the four major ligaments of the knee.It connects from a posterio-lateral part of the femur to an anterio-medial part of the tibia. These attachments allow it to resist forces pushing the tibia forward relative to the femur.More specifically, it is attached to the depression in front of the intercondyloid eminence of the tibia, being blended with the anterior extremity of the lateral meniscus.It passes up, backward, and laterally, and is fixed into the medial and back part of the lateral condyle of the femur.

Tuesday, July 10, 2007

Function of the Knee

In human anatomy, the knee is the lower extremity joint connecting the femur and the tibia. Since in humans the knee supports nearly the entire weight of the body, it is the joint most vulnerable both to acute injury and to the development of osteoarthritis.

The knee functions as a living, self-maintaining, biologic transmission, the purpose of which is to accept and transfer biomechanical loads between the femur, tibia, patella, and fibula. In this analogy the ligaments represent non-rigid adaptable sensate linkages within the biologic transmission. The articular cartilages act as bearing surfaces, and the menisci as mobile bearings. The muscles function as living cellular engines that in concentric contraction provide motive forces across the joint, and in eccentric contraction act as brakes and dampening systems, absorbing loads.

Monday, July 9, 2007

About The Knee

The knee is my favorite joint but is commonly injured in all age groups, especially during athletics and exercise. Physicians can frequently diagnose many knee complaints by first taking a thorough history from the patient, which often reveals a twisting episode, swelling, popping, grinding, giving way or locking. It's also important to know whether the injury is recent or recurrent and if any treatment, tests, or surgery have been done in the past.

Although there are many complicated areas around the injured knee that doctors are concerned about, the most commonly affected structures are the cartilage (menisci) and ligaments. These are found on each side of the joint and there are two other ligaments that cross inside the knee, known as cruciates.

On physical exam, I ask the patient to point to the spot where and when it hurts the most. I'm looking for swelling in the tissues, fluid in the joint, muscle wasting, kneecap grinding, ligament instability, or loss of motion, just to name a few. The knee joint is quite easy to examine and experienced physicians will not cause excessive discomfort to the patient during these maneuvers. X-rays do not show ligament or cartilage damage and are frequently over-utilized with multiple views. Stress x-rays are unnecessary and painful for the patient. Likewise, Magnetic Resonance (MR) scans can be helpful but are not necessary unless the physician feels strongly that the outcome of the scan will contribute to or change the proposed course of treatment.

Although many problems about the knee can be treated conservatively with early mobilization, ice, rehabilitation, Physical Therapy , and NSAIM, some conditions such as cartilage tears will require arthroscopic surgery. This procedure is done as an out-patient, is quite safe, and has a low complication rate, allowing most patients a quick return to work and recreational activities.

Ligament tears may also require surgical intervention but a thorough discussion of the pros and cons of the procedure, type of repair and graft origin, length of rehabilitation, need for post-operative bracing, and close follow-up care is essential. Make sure you clearly understand what you're getting yourself into which is why I frequently encourage prospective surgical candidates to contact some of my previous patients who have had the same procedure done to find out all the specifics and whether they would do it all over again. Virtually all these operations can be done as out-patients.

Bursitis and tendinitis occurring about the knee are usually treated with NSAIM, ice, Physical Therapy modalities, and possible modifications of activities.

Chondromalacia, or a roughening of the undersurface of the kneecap, is commonly seen in females more than males and can be treated symptomatically with ice and eexercise but may require surgical attention in patients with excessive grinding or pain who have failed to respond to conservative measures. The laser has made this procedure more successful and you should ask your doctor if he uses this equipment and has had the proper training.

Cartilage repair and transplantation is being heavily investigated at this time but currently has limited use on lesions around the knee, specifically the femur, and the technique requires two procedures, one of which is quite extensive.

Finally, many patients ask about braces for knees. Legitimate braces with metal or plastic parts are frequently required after ligament injuries or surgery and are custom fitted. I like to reserve the use of these braces for people with instability or who are post-operative from ligament surgery. Patients who have no instability may want to purchase sleeves or other slip-on devices which are fine but should not be worn too tight as to compromise circulation.

Sunday, July 8, 2007

Anatomy of Knee

The knee is a complex, compound, condyloid variety of a synovial joint which hovers. It actually comprises two separate joints.

The femoro-patellar joint consists of the patella, or "kneecap", a so-called sesamoid bone which sits within the tendon of the anterior thigh muscle (m. quadriceps femoris), and the patellar groove on the front of the femur through which it slides.

The femoro-tibial joint links the femur, or thigh bone, with the tibia, the main bone of the (lower) leg. The joint is bathed in a viscous (synovial) fluid which is contained inside the "synovial" membrane, or joint capsule.

The recess behind the knee is called the popliteal fossait can also be called a "knee pit."

Saturday, July 7, 2007

Commonly Tests Of Knee

Commonly Tests Of Knee

X-Ray (radiography)

A procedure in which an x ray beam is passed through the knee to produce a two-dimensional picture of the bones.

Computerized axial tomography (CAT) scan

A painless procedure in which x rays are passed through the knee at different angles, detected by a scanner, and analyzed by a computer. CAT scan images show soft tissues such as ligaments or muscles more clearly than conventional x rays. The computer can combine individual images to give a three-dimensional view of the knee.

Bone scan (radionuclide scanning)

A technique for creating images of bones on a computer screen or on film. Prior to the procedure, a harmless radioactive material is injected into your bloodstream. The material collects in the bones, particularly in abnormal areas of the bones, and is detected by a scanner.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

A procedure that uses a powerful magnet linked to a computer to create pictures of areas inside the knee. During the procedure, your leg is placed in a cylindrical chamber where energy from a powerful magnet (rather than x rays) is passed through the knee. An MRI is particularly useful for detecting soft tissue damage.

Arthroscopy

A surgical technique in which the doctor manipulates a small, lighted optic tube (arthroscope) that has been inserted into the joint through a small incision in the knee. Images of the inside of the knee joint are projected onto a television screen.

Joint aspiration

A procedure that uses a syringe to remove fluid buildup in a joint, and can reduce swelling and relieve pressure. A laboratory analysis of the fluid can determine the presence of a fracture, an infection, or an inflammatory response.

Biopsy

The examination of a piece of tissue under the microscope.

Friday, July 6, 2007

How Are Knee Problems Diagnosed?

How Are Knee Problems Diagnosed?

Doctors diagnose knee problems based on the findings of the medical history, physical exam, and diagnostic tests.

Medical history

During the medical history, the doctor asks how long symptoms have been present and what problems you are having using your knee. In addition, the doctor will ask about any injury, condition, or health problem that might be causing the problem.

During the medical history, the doctor asks how long symptoms have been present and what problems you are having using your knee. In addition, the doctor will ask about any injury, condition, or health problem that might be causing the problem.

Physical examination

The doctor bends, straightens, rotates (turns), or presses on the knee to feel for injury, and determine how well the knee moves and where the pain is located. The doctor may ask you to stand, walk, or squat to help assess the knee’s function.

The doctor bends, straightens, rotates (turns), or presses on the knee to feel for injury, and determine how well the knee moves and where the pain is located. The doctor may ask you to stand, walk, or squat to help assess the knee’s function.

Diagnostic tests

Depending on the findings of the medical history and physical exam, the doctor may use one or more tests to determine the nature of a knee problem.

Depending on the findings of the medical history and physical exam, the doctor may use one or more tests to determine the nature of a knee problem.

Thursday, July 5, 2007

Knee: Muscles

Muscles

There are two groups of muscles at the knee. The four quadriceps muscles on the front of the thigh work to straighten the knee from a bent position. The hamstring muscles, which run along the back of the thigh from the hip to just below the knee, help to bend the knee.

Tendons and ligaments

The quadriceps tendon connects the quadriceps muscle to the patella and provides the power to straighten the knee. The following four ligaments connect the femur and tibia and give the joint strength and stability:

There are two groups of muscles at the knee. The four quadriceps muscles on the front of the thigh work to straighten the knee from a bent position. The hamstring muscles, which run along the back of the thigh from the hip to just below the knee, help to bend the knee.

Tendons and ligaments

The quadriceps tendon connects the quadriceps muscle to the patella and provides the power to straighten the knee. The following four ligaments connect the femur and tibia and give the joint strength and stability:

The medial collateral ligament (MCL), which runs along the inside of the knee joint, provides stability to the inner (medial) part of the knee.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL), which runs along the outside of the knee joint, provides stability to the outer (lateral) part of the knee.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), in the center of the knee, limits rotation and the forward movement of the tibia.

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), also in the center of the knee, limits backward movement of the tibia.

The knee capsule is a protective, fiber-like structure that wraps around the knee joint. Inside the capsule, the joint is lined with a thin, soft tissue called synovium.

Wednesday, July 4, 2007

What Are the Parts of the Knee?

Tuesday, July 3, 2007

Knee : Bones and Cartilage

Bones and Cartilage

The knee joint is the junction of three bones: the femur (thigh bone or upper leg bone), the tibia (shin bone or larger bone of the lower leg), and the patella (knee cap). The patella is 2 to 3 inches wide and 3 to 4 inches long. It sits over the other bones at the front of the knee joint and slides when the knee moves. It protects the knee and gives leverage to muscles.

The ends of the three bones in the knee joint are covered with articular cartilage, a tough, elastic material that helps absorb shock and allows the knee joint to move smoothly. Separating the bones of the knee are pads of connective tissue called menisci (men-NISS-sky). The menisci are two crescent-shaped discs (each called a meniscus (men-NISS-kus) positioned between the tibia and femur on the outer and inner sides of each knee. The two menisci in each knee act as shock absorbers, cushioning the lower part of the leg from the weight of the rest of the body as well as enhancing stability.

Monday, July 2, 2007

Knee Joint Basics

Knee Joint Basics

The point at which two or more bones are connected is called a joint. In all joints, the bones are kept from grinding against each other by lining called cartilage. Bones are joined to bones by strong, elastic bands of tissue called ligaments. Muscles are connected to bones by tough cords of tissue called tendons. Muscles pull on tendons to move joints. While muscles are not technically part of a joint, they’re important because strong muscles help support and protect joints.

Sunday, July 1, 2007

What Do the Knees Do? How Do They Work?

What Do the Knees Do? How Do They Work?

Several kinds of supporting and moving parts, including bones, cartilage, muscles, ligaments, and tendons, help the knees do their job. (See Joint Basics, below.) Each of these structures is subject to disease and injury. When a knee problem affects your ability to do things, it can have a big impact on your life. Knee problems can interfere with many things, from participation in sports to simply getting up from a chair and walking.

The knee is the joint where the bones of the upper leg meet the bones of the lower leg, allowing hinge-like movement while providing stability and strength to support the weight of the body. Flexibility, strength, and stability are needed for standing and for motions like walking, running, crouching, jumping, and turning.

Several kinds of supporting and moving parts, including bones, cartilage, muscles, ligaments, and tendons, help the knees do their job. (See Joint Basics, below.) Each of these structures is subject to disease and injury. When a knee problem affects your ability to do things, it can have a big impact on your life. Knee problems can interfere with many things, from participation in sports to simply getting up from a chair and walking.

by DrKnee

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)